Climate Change, Hand Papermaking, Plasticane™: Artist Interview with Hannah Chalew

Plastic trash. Petrochemical industries that pollute landscapes and people. Sugarcane refining, and the legacy of chattel slavery. Hand paper making process allows artists to transform fibers into new material—paper that can bring an ecosystem of very real issues into tangible form.

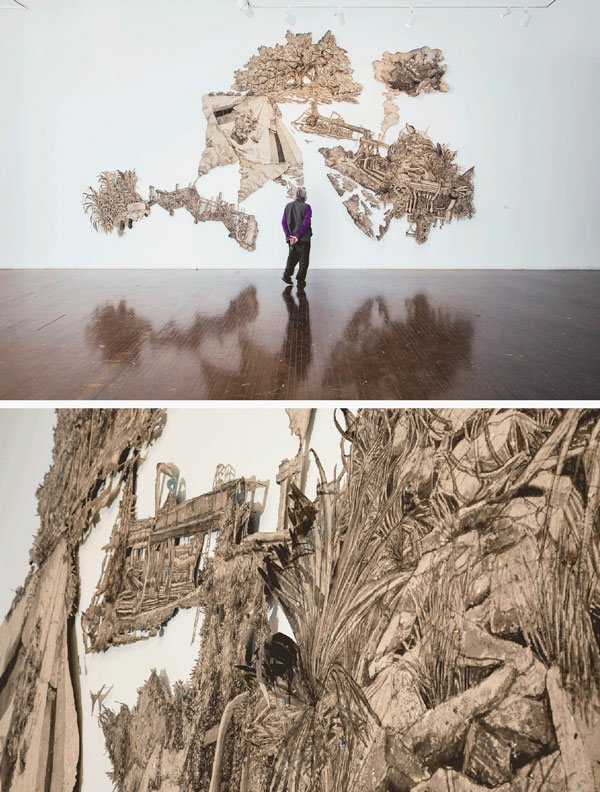

Hannah Chalew is a New Orleans based artist whose artwork and studio practice address human-caused climate change. She creates incredible large scale drawing installations made from plasticane™, a blended paper of bagasse (sugarcane byproduct) and plastic waste.

Luckily for you, Chalew kindly agreed to answer my questions, so keep on reading for the full interview. Enjoy! - May Babcock

MAY BABCOCK: What is your background? How did you initially become interested in hand papermaking?

HANNAH CHALEW: I grew up in New Orleans and had the incredible opportunity to attend the New Orleans Center for Creative Arts for high school, which I really credit as my artistic foundation. I’ve been drawing and painting since I was very young, and decided to pursue being an artist after realizing in college that a degree in anthropology was about as relevant to the real world as a degree in studio art. So I majored in Studio Art and minored in Anthropology and have been working on making art full-time ever since.

Before grad school, my practice was very centered around making drawings on paper, and when I was applying to Cranbrook, where I got a degree in Painting in 2016, the painting mentor, Bev Fishman asked me why I wasn’t making my own paper. While in Detroit, I was lucky enough to work with the talented artist and paper-maker, Meg Heeres, and she taught me how to make paper and has been really generous over the years helping me troubleshoot process issues, etc. So ever since grad school, I’ve been exploring hand papermaking as a way to make my drawings more intentional and really connect the subject of the drawings to the ground of the paper; to literally imbue my medium with my message.

MB: I really enjoyed the video you shared of large-scale papermaking — can you describe your technical approach for us?

HC: Since 2016, I’ve been trying to figure out how to make large sheets of paper. I tried making larger screens and also working with a few people to pull one large sheet, but ultimately I found success by tiling pieces pulled from with my handy 12” square screen. My studio process is pretty scrappy and DIY, but it really fits the medium of pulp made from trash. Before I start making the paper, I have mostly settled on the composition for the future drawing. I lay big moving felts on the ground and sketch out the outline of the piece I’m trying to make. Then I start pulling sheets of paper and collaging them into that shape. After I press the sheets overnight, I paint methyl cellulose across the seams of the overlapped pieces to give the finished sheet more strength.

MB: Your paper works such as Root Shock II have used trash and abaca. And more recently, Refining Patterns has transitioned to paper made from sugarcane and shredded plastic, what you’ve named plasticane™. Can you elaborate on the significance of your fiber and material choices, and how they have evolved in your practice? How did you arrive at plasticane™?

HC: Since moving home to Louisiana in 2017, I’ve been thinking a lot more about the ways the people and landscape here have been exploited over time, and specifically examining the connections between the plantation era and our petrochemical age. Just upriver from New Orleans is a dense petrochemical refining region that people call ‘Cancer Alley’ because of the grave health problems the local populations experience. These people are mainly poor people of color who have lived in that region ever since their ancestors were emancipated from slavery; they were living in vibrant communities until industry sprung up all around them. Petrochemical industries took over the sites of nearby former plantations and have been poisoning the surrounding neighborhoods ever since. Living down the Mississippi River in New Orleans, my health risks are less acute, but I wanted to make work that would draw attention to these issues, and connect them to those of us that are downriver and downwind, but ultimately bound in the networked ecologies that tie us all together.

I had been using abaca for a while. I love how strong it is: you can add a small amount of it to really any kind of fiber and the resulting paper will be really strong. But as I have been trying to get more intentional about the materials I choose and also wanting to use materials that are as sustainable as possible, I began to think about the possibility of sugarcane, which is ubiquitous in Louisiana. In the bible of Papermaking with Plants, Lilian Bell has a recipe for making paper from bagasse, the waste product from sugarcane grinding, and she cites paper being made from sugarcane in Louisiana in the 1850s! I got really excited about the historical connections of sugarcane, which was a staple chattel slavery crop and also one of the most dangerous crops for the slave who were forced to harvest and process it. Sugarcane is still a big crop in Louisiana, and once the refineries grind the sugarcane, the byproduct called bagasse gets piled up in mountains behind the refineries and is seen as a waste product. But for me it has become a renewable resource.

"To me, this is the most thrilling thing about paper-making: how you can combine water and different fibers and alchemically create a new material."

To connect the legacy of sugarcane on this landscape with the petrochemical industry, I decided to add shredded plastic to the cooked and beaten bagasse. The U.S. is now one of the biggest producers of natural gas, from harmful fracking processes in Louisiana and elsewhere nationally. One of the byproducts of natural gas production is ethylene, which, after being processed very toxic refining in places like Cancer Alley, becomes plastic. Given plastic’s ubiquity as street litter in New Orleans, I also see plastic waste as a renewable resource.I’ve been really excited about the results of this new paper, which I call plasticane™. To me, this is the most thrilling thing about paper-making: how you can combine water and different fibers and alchemically create a new material. In the larger-scale drawings, viewers see bits of color and shininess amidst the drawing, but can’t really understand the material until they get close. Then the beautiful drawing breaks down, and hopefully they have a visceral reaction to the material, recognizing some of the trash and rethinking the whole experience.

MB: The Refining Patterns artist statement addresses the extractive economies of petrochemical industries and sugarcane refining in Southern Louisiana, exploring both the legacy, present, and future of these systems. What is the relationship between these ecosystems and the ecosystem of processes in your studio, in particular, papermaking process?

HC: My process and where I get my materials have become very important to me. In the past few years, it has become part of my studio practice to collect trash in the streets around my studio. This practice grounds me in the surrounding neighborhood, and while I am collecting raw materials for art-making, I’m also performing a micro-act of environmental stewardship and deterring future dumping. What I can’t recycle, I will add into my sculptures, and I shred the thinner bits of unrecyclable plastic I find—chip bags, condom wrappers, Styrofoam plates, etc.—to be the “plasti” in the plasticane™.

"...it has become part of my studio practice to collect trash in the streets around my studio. This practice grounds me in the surrounding neighborhood, and while I am collecting raw materials for art-making, I’m also performing a micro-act of environmental stewardship..."

The first batch of bagasse I collected was from the Lula Refinery in Belle Rose, which happened to be on my route when I was doing some water-protecting as a monitor for construction of the Bayou Bridge pipeline, the tail-end of the Dakota Access Pipeline that is set to terminate in the heart of Cancer Alley. So that provenance really connects bagasse to the oil and gas industry. The cooking and beating of the bagasse and the water used for paper-making are the most fossil-fuel-intensive processes of my paper-making practice. Since 2018, I’ve been working to divest my studio practice from fossil fuels to really ground the message of my work with real action toward a livable future. But I do use propane to cook the bagasse. I’m researching alternative methods (and would appreciate tips from your readers). I have a 2.2 lb Hollander beater that I use to beat the bagasse. In the past year I received a grant to produce a solar “cart” that harvests solar power as well as rainwater. This cart has been powering an outdoor installation, but I recently moved it to my studio and am very excited to use the solar power to power my beater and use the harvested rainwater for papermaking. I’ve honed the papermaking process so that I can make large sheets (8’ x 10’) in about 2 hours. I find this process very meditative and really enjoy the physical engagement with the materials. I love the aleatoricism of the process, seeing where the plastic bits surface after each pull and embracing the lack of control. Despite the fact that I plan my drawings beforehand, they change a lot in response to the texture of the paper and the way the materials integrate with each other. I press the paper with big sheets of plywood and cinder blocks and then back the paper with recycled bed sheets to give them strength and so that I can roll the drawings for easy transport and storage. The rolling and unrolling of the drawings also add an element of aging and wear to the work that becomes part of the drawings as well.

MB: The ink drawings are stunning! The level of detail, the play of depth, and their ability to force one’s eye to constantly engage and travel — trying to make sense of form and image. Without reading a statement or even the title, one notices absent humans, but pipelines and plastics remain, entangled with plants. One, what is your source imagery? And two, what do you hope the biggest takeaway is for viewers?

HC: I bike to and from my studio and draw a lot of inspiration from those rides and particularly from abandoned lots in New Orleans that have become this harbinger for me of a future without us, where the swamp and trash dump sites commingle to become new wild ecosystems. I also often pick up interesting found materials on these rides. I also take a lot of reference photos when I am doing environmental justice work in Cancer Alley. Using photoshop, I collage together the different imagery to create the compositions for my drawings.

One of the reasons I’ve been wanting to make large sheets of paper is so that, from afar, viewers will see the drawing and be drawn in by the beauty and want to explore the details. And then when they are closer the drawing breaks down and they see the roughness of the surface and hopefully recognize some of the plastic detritus, a recognizable shred of a Cheetos bag or flake of Styrofoam and become both implicated—we all use these products— and disgusted. I’m very interested in harnessing the power of beauty to keep viewers engaged so they are able to have the slower burn of realization of the materials and also sit with the sadness of this future landscape, and ultimately think about what their relationship is to these issues and what changes they can make in their life and beyond. I believe that art has power, the power to make people feel emotions and to reach them in new ways. I hope that my work can bring awareness to issues and create a visceral and tangible connection to problems that seem really big and abstract. I believe that shifting people’s perspectives on the issue of climate change is essential to creating the real change we will need to make to ensure a livable future. But I also recognize that these psychological shifts need to be paired with individual and collective action, so more and more I’ve been exploring ways to connect my artwork with real ways for viewers to plug in to these issues.

For the show, “No Man’s Land” that Refining Patterns was a part of, it was really important for the other artists and myself to connect our artwork with action items for viewers to take away. For our opening, we partnered with 350 New Orleans, a local branch of a global climate activist group, to present a lecture on coastal land-loss and ways to plug in to the work they are doing to combat it. We also purchased renewable energy credits to offset the energy needs of the gallery for the month of our exhibit and provided resources to connect people with local wind-power energy providers.

MB: How does the experience of working on paper that you made differ from drawing on machine-made paper, if at all? How does the handmade surface affect your drawing?

HC: So different! I really can’t draw on machine-made paper anymore. I love how my handmade paper becomes another element of the drawing, just as much as the ink that I lay over it. I used to make really detailed drawings on nice printmaking paper, in the 30” x 40” range. When I started experimenting with papermaking, especially with the embedded bits of plastic, I found that to get the level of detail I wanted, I needed to scale up. I can’t use the .25 technical pens I used to favor; now I use refillable felt tip pens and ink washes. But I love reacting to the surface of the paper and incorporating the plastic into the drawings or fighting against it. All of these decisions become a part of the story of the drawing.

MB: Why cut the paper? How does that choice change how the works live in a space, and how we view the drawings?

HC: Another reason I abandoned machine-made paper was that I wanted to break the rectangle and the idea of landscape drawing as a window into a world and instead have the drawing become that world. By cutting the paper and then mounting the pieces on nails so they float an inch or two away from the wall, the drawings become more sculptural, more like objects, or specimens, because they are really embodying materially the subject matter I’m referencing. The cutting also allows the paper to bend and curl and flop in different ways, further blurring the line between drawing and sculptural object.

MB: Can you expand on the connections between your immersive installations and drawings on paper?

HC: My installations and my drawings really feed into and inform each other. I love my studio practice the most when I’m not blinded by a specific deadline and I am able to move freely between drawings and installations, and when they can be having a dialogue together in my studio. More and more the materials are becoming the same in my installations and my drawings, but I process them more for papermaking.

Recently, I’ve been thinking of ways to further bring together the drawings and the installations. Right now, I feel that my installations are more successful in creating immersive and visceral experiences, and I’m thinking of ways to bring that immediacy and emotion into drawings more.

MB: What future directions are you working towards?

HC: Right now, I’m working on making my drawings more sculptural and pushing them further from the wall. I also am trying to make them a bit more disgusting, by adding more plastic to the ratio so that when the viewer comes closer into the drawings they will have a stronger reaction to the material. I’ve also been experimenting with adding living plants into the drawings and creating situations where the drawing and plants can collaborate. I’m also working on securing public space to do longer-term outdoor installations and developing a new iteration of the solar cart that would have a built-in space where I could hold outdoor papermaking workshops and draw connections between the renewable resources of solar power and rainwater harvesting, my sculptural materials, and how papermaking from recycled pulp or sustainable plant fibers using rainwater can be a hands-on application that brings together all of these ideas.

Follow Hannah Chalew on Instagram

Explore more of her work on her artist website